Market Demand and Pest Problems Prompt Rialto, CA Citrus Grower with Deep Roots to Diversify Offering

June 28, 2016 | Kate Edwards

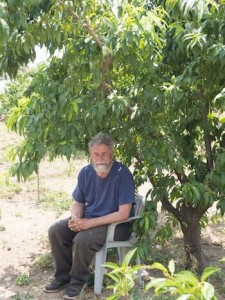

John Adams of Adams Acres, a 109-year-old family farm in Rialto. Photo by Kate Edwards

John Adams has deep roots in the Rialto, California citrus grove known as Adams Acres. His great-grandmother bought the original 20 acres back in 1899, and his grandfather put in the orange grove in 1907. Adams, now 72 years old, has spent most of his life on this land, growing and tending to the last orange grove in an area that used to boast some 6,000 acres of commercial citrus.

Today, Adams is down to just two acres and change on which sits the original farmhouse, a century-old stone outbuilding and an antique tractor. Ten of the original 20 acres were sold off to developers in the 1970s, and just this year, Adams was forced to sell about three-quarters of the remaining land. He sold it to yet another developer who is planning to build, as he says drily, “a gated community of houses set three feet apart.”

Adams sold the land for financial reasons. The wholesale price for Valencias, the oranges used in most commercial juice production, has been depressed worldwide for decades due to fading demand coupled with the influx of cheap fruit from Brazil, Chile and South Africa. This means that the local packing house stopped purchasing his crop awhile ago, and the citrus sales at his roadside stand weren’t enough to make up the difference.

There is also the looming threat of the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP), a pest that infects citrus trees and eventually interferes with fruit production to the point that it becomes bitter, misshapen and inedible. Native to tropical and subtropical areas of Asia, the psyllid was discovered in Florida in the late 1990s, and is now, as Adams puts it, “causing havoc in Florida and cutting production by about half.” To date, the pest has been found in southern states like Texas, Georgia, Arizona and Louisiana–and in central and southern California.

Government-led eradication efforts have included parasitic wasps, spraying and systemic poisons, but Adams is skeptical of such efforts due in part to his own past experience. He worked for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for a few years after getting his doctorate in Soil Sciences from UC Riverside. He describes his time at the BLM as being akin to, “playing a straight man in a Marx Brothers movie,” and clearly has little faith in the government’s ability to stem the tide of the ACP.

In light of these developments, Adams decided to diversify and plant non-citrus fruit trees such as peaches, apricots and apples. But he didn’t stop with the well-known varieties–he also went for the new and/or unusual. The result is about 200 new trees encompassing roughly 100 different varieties of figs, cherries, pomegranates and peaches, as well as exotic fruits like nectaplums, Pakistani mulberries, tejocotes and Red Malaysian guavas.

When choosing what to put in, Adams, a trained botanist, gambled on the chill requirements (annual hours of sub-45 degree temps) of the trees he chose. However, Rialto’s chill hours are a small percentage of what they were decades ago when, as he remembers, “We’d get cold north winds blowing like crazy here [and] it’d be in the low 40s for days!” Thanks to global warming, which Adams states vehemently, “is here and it’s real,” as well as the higher temperatures brought on by all the surrounding development, the area now gets just about 160-170 chill hours a year. That should make a lot of trees untenable for Adams’ grove.

Or so you’d think. In reality, and this is where it becomes clear that Adams Acres is now what one fruit stand visitor calls, “an experimental station,” many of the new trees are bearing significant fruit despite the lack of adequate chill hours. As Adams says while pointing out tree after tree that shouldn’t bear fruit, but does, “We are finding out things here that no one else knows, and it is surprising stuff!” He says, “I’ve got an elephant heart plum just loaded with plums. I thought it might not produce at all,” due to a stated chill requirement of ‘500 chill hours or less’. It got a lot less this year. Then there is the sweeter-than-sweet ‘Tropic Snow’ white peach with its chill requirement of 200 hours annually. The tree didn’t even come close, yet the fruit is ready to pick. (Those trees not doing so well are being moved to a fellow grower’s colder and higher farm in some nearby hills.)

Adams’ experimentation hasn’t stopped at trees. In search of added income, he decided to plant winter vegetables in the shade between the rows of trees. “You’d think they could not grow at all, but they did,” he says, “They grew slower, but they grew, and they were sweeter and more tender than those that grow in the sun.” After that, he found a wholesaler willing to pay top dollar for all the rhubarb they could grow.” Adams says, “That conks out in the sun, so we’ll grow it in the shade.”

Tidy rows of vegetables grow in the shade between the exotic fruits at Rialto’s Adams Acres. Photo by Kate Edwards

While Adams says that he has slowed down in recent years, and he “used to look at every tree, every day, but I’m 72 years old. It makes a difference–your legs go,” it is obvious he has no intention of ever retiring. As for after he goes, he has a (much younger) farmer already picked out who will take over and continue the business. Adams Acres is going to be around for awhile yet.

Submit a Comment